FERRET DECLINE

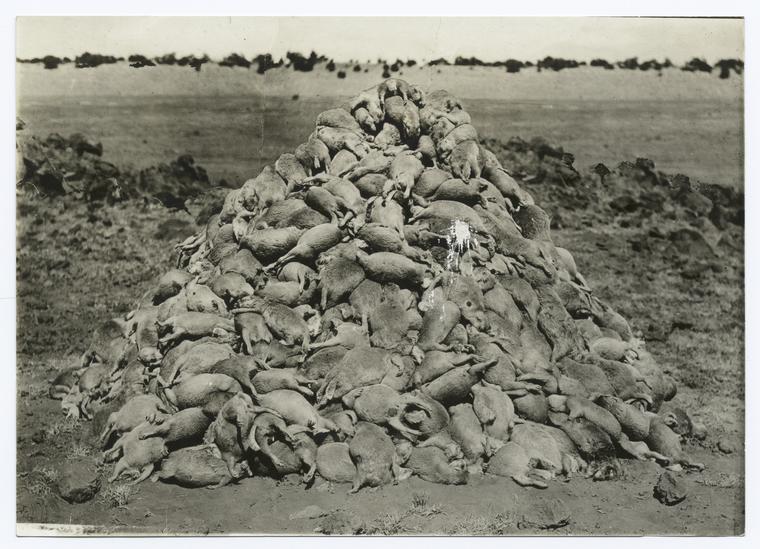

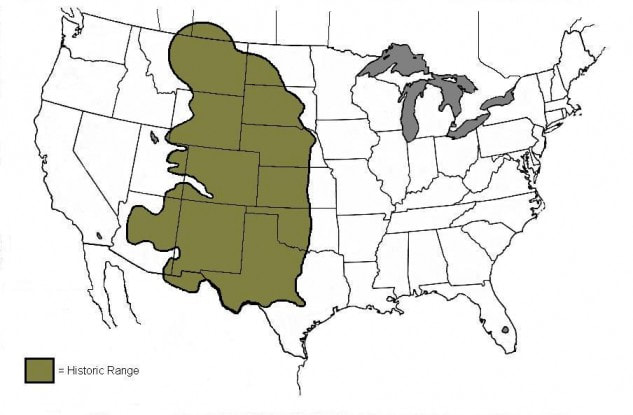

The black-footed ferret is thought to have been common on prairie ecosystems prior to European settlement of western North America. However, starting in the 1900s, ferret populations experienced a devastating decline so dramatic that the species was thought to be extinct by early 1970s until a single extant population was rediscovered in 1981. The causes for these declines are due to a combination of factors including habitat loss and disease described in detail below.